If you’re an information security practitioner, or just keep up with cybersecurity reporting, you have almost certainly seen QakBot mentioned in your news feeds recently. And if you’re keeping tabs on the Tidal blog, you recently read about how adversaries are evolving their tactics, techniques, and procedures (“TTPs”) at alarming rates. In this blog, we will discuss why most organizations should care about QakBot, and how it represents a clear example of adversary TTP evolution (and the importance of threat-informed defense). We’ll also show how Tidal’s free Community Edition can help identify the latest TTPs associated with threats like QakBot, and give practical, actionable guidance for defending against these adversary behaviors. Explore the Community Edition here, and don’t forget to create an account to save and customize the QakBot Technique Sets shared below and to engage others in the threat-informed defense space in our Community Slack!

What is QakBot, and Why is it a Concern?

In our view, most organizations should include QakBot in their threat profile, a register of the most notable cyber threats relevant to the organization and its industry. QakBot (also known as QBot and Pinkslipbot) is a prolific malware tied to a large number of attacks since its debut in 2007. Historically, QakBot operators have executed intense campaigns (individual vendors can see 1,000+ detections per month), followed by lulls in activity. QakBot has attacked victims in virtually every major industry.

QakBot was originally designed as a banking Trojan, a type of malware built to steal financial information, but it now includes many “modules” that broaden its functionality. Notably, in recent years, security teams have observed QakBot being used in association with malware designed for a range of other purposes, including pre- and post-infection activities. These include other prolific malware responsible for attacks on victims in very many industries, such as Cobalt Strike, Emotet, and Brute Ratel. Security teams typically use factors like these to further elevate a threat’s priority level within their threat profile.

QakBot: A Case Study in TTP Evolution

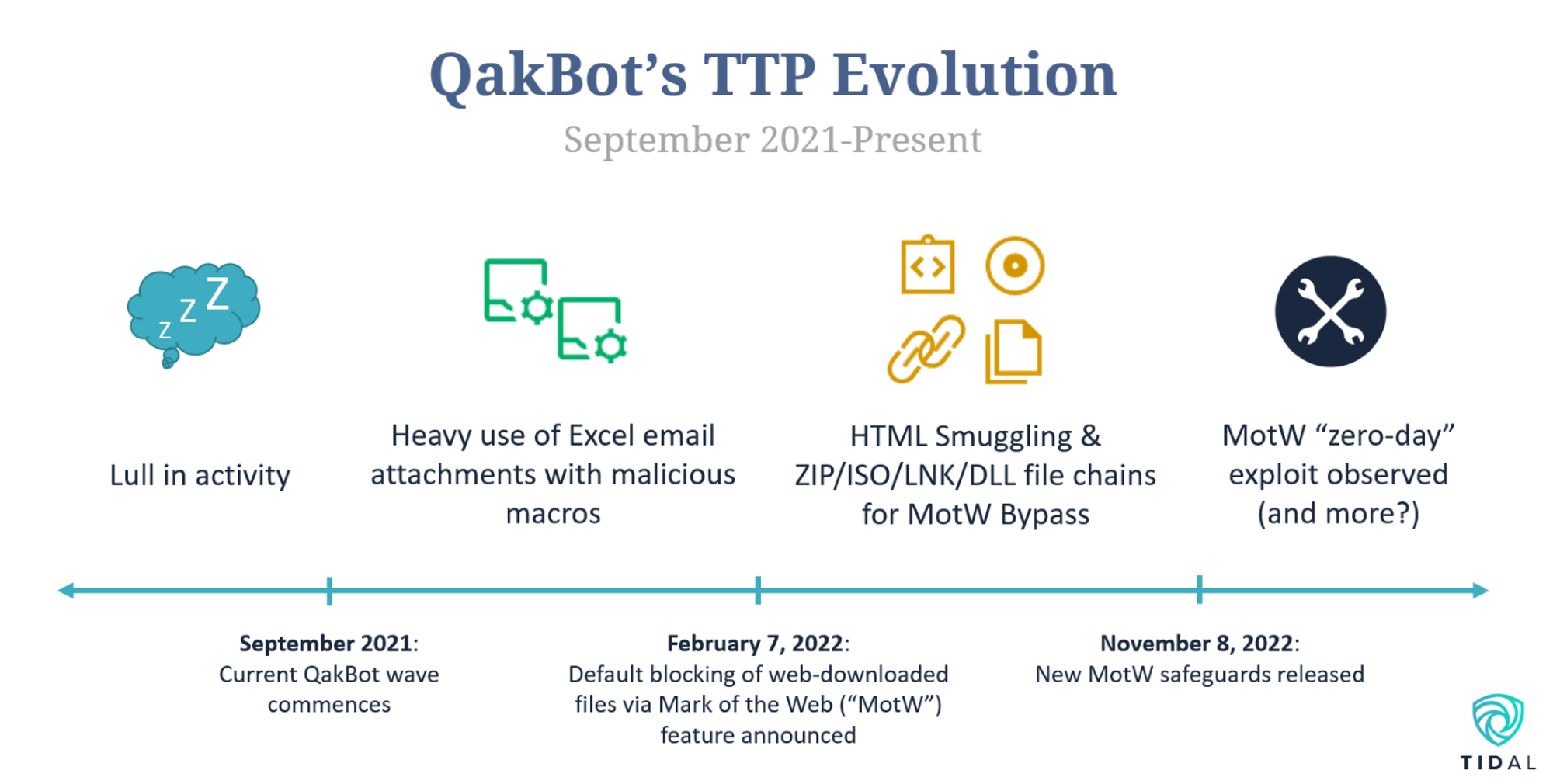

As we highlighted in our last blog, adversaries are increasingly demonstrating the ability to modify their behaviors, in some cases with incredible speed. QakBot represents a clear example of this trend. After a lull in activity last summer, QakBot operators resumed attacks in September 2021. QakBot infections at the time relied heavily on malicious Excel email attachments containing macros, which serve as efficient means of automating malicious command execution built into common file types. In direct response to frequent macro abuse by QakBot and other threats, Microsoft announced in February 2022 that it would begin to block macro execution in popular Microsoft Office file types when those files were downloaded from the Internet, which includes files attached to or linked within spam emails like those frequently delivered during QakBot campaigns. This new security measure is achieved by assigning a hidden value, known as Mark of the Web (“MotW”), to files originating from the Internet.

QakBot operators appeared to adapt to this significant new security measure and began to implement alternative infection techniques to bypass these MotW protections for Office files almost immediately. Researchers from Hornetsecurity began to observe QakBot spam emails now containing HTML attachments, which provide a stealthy means of downloading additional files (in this case ZIP files) that contained multiple other file types (ISOs, LNKs, and DLLs), which were accessed sequentially to ultimately run the main QakBot executable. The Hornetsecurity researchers witnessed a major drop in the rate of Excel email attachments, from 22% of all malicious attachments in March to just 4% in September, while Proofpoint researchers observed a dramatic rise in the prevalence of ISO email attachments and campaigns involving LNK files beginning in March and February, respectively (as well as a large drop in macro-enabled email attachments starting in March).

With the November 8 Patch Tuesday updates, Microsoft took further steps to address some of these techniques, announcing that MotW security features would propagate to relevant files contained within ISO files, among other relevant fixes. However, just six days after this announcement, QakBot appeared to evolve its technique set once again, as security teams observed QakBot infections involving files crafted to bypass some of these latest protections. Interestingly, QakBot operators may have adopted this latest defense evasion method from other threat actors, as the infection vector was recently observed in a campaign involving Magniber ransomware.

Defending Against QakBot’s Evolving TTPs

QakBot’s repeated TTP evolution over the past year alone highlights why a threat-informed approach to defense is absolutely necessary; without intelligence around QakBot’s current techniques, you could be focusing defensive resources on techniques that are now less relevant (an especially impactful issue if QakBot is one of the top-priority adversaries in your threat profile). Let’s now take a look at how Tidal’s free Community Edition can help identify techniques – and, importantly, relevant defensive capabilities – associated with QakBot’s recent TTP evolutions.

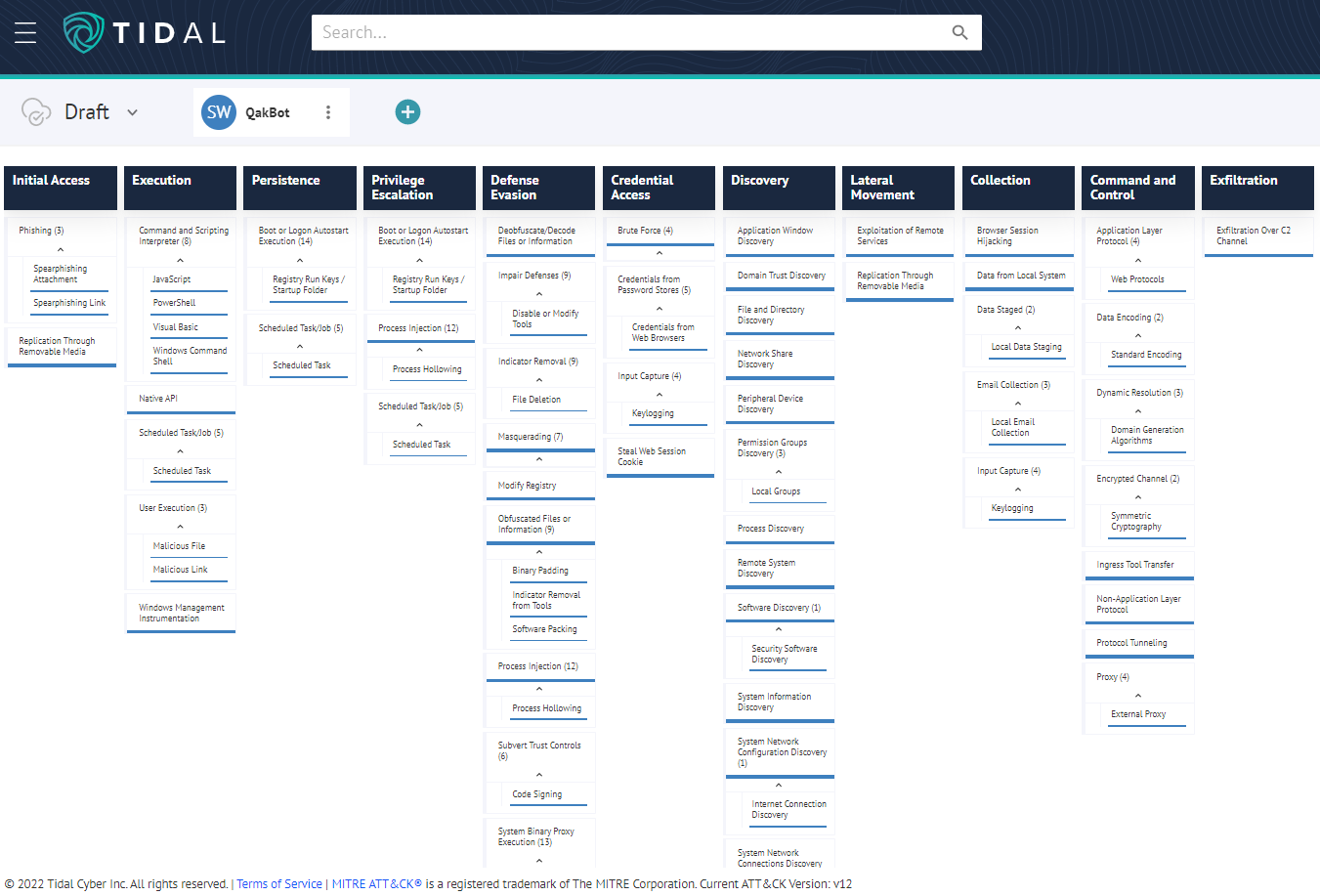

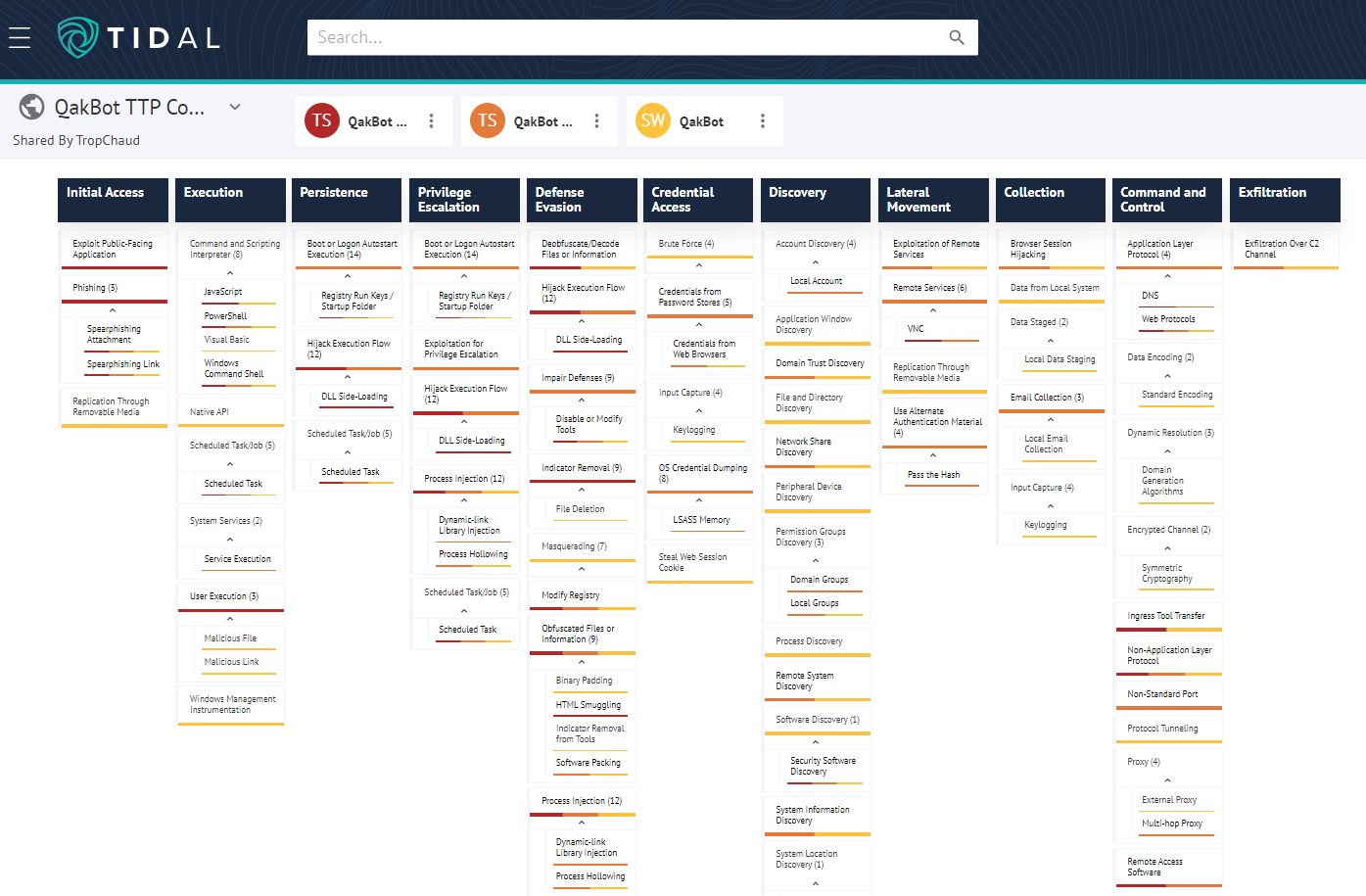

For a historical baseline, we can begin by loading the set of techniques associated with QakBot from the MITRE ATT&CK® knowledge base into Tidal’s matrix view. This set covers 64 techniques linked with QakBot based on nine public reports from June 2020 to September 2021:

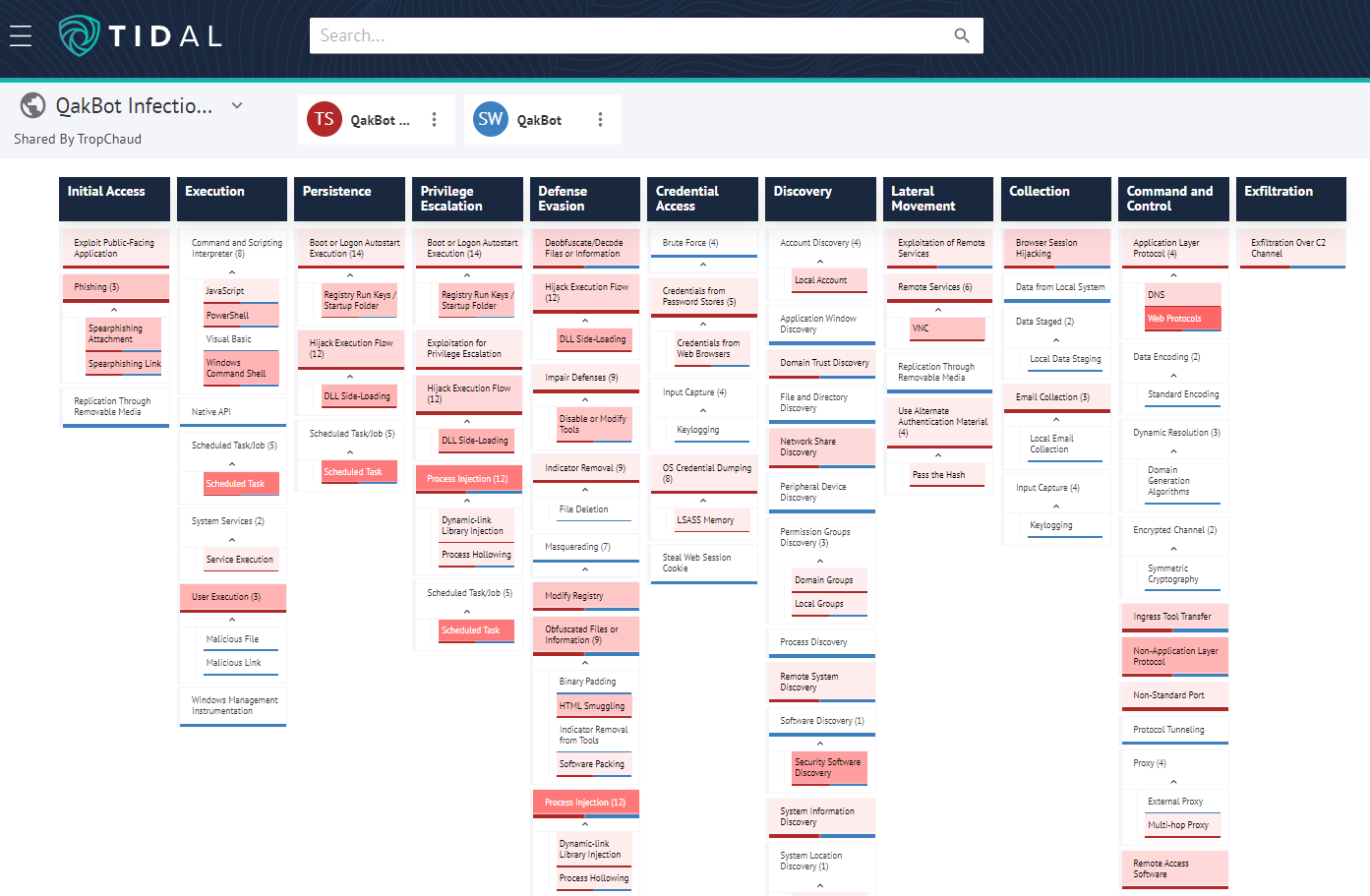

Next, let’s examine the body of more recent public threat intelligence around QakBot. For these examples, I compiled custom Tidal Technique Sets based on 16 reports that I could quickly surface online and which had readily identifiable technique details – certainly not the full body of QakBot reporting since last year, but a good amount to show depth within the technique data. Overlaying the custom technique set, which also comprised 64 techniques, onto the ATT&CK knowledge base set revealed 37 techniques which were exclusively referenced in the most recent QakBot intelligence reporting (October 2021-October 2022). The darker shades of red represent references in more reports in the recent dataset, with a range of one to eight reports:

This final view rearranges the same technique datasets discussed above into three sets of techniques organized by time period: the ATT&CK knowledge base, which covers June 2020-September 2021 reporting (yellow), October 2021-March 2022 (orange), and April 2022-October 2022 (red). This visual helped surface techniques that were newly reported during each of the recent phases of QakBot’s TTP evolution (prior to the current activity waves starting last fall, and before and after the period around the macro-blocking announcement this year), to more accurately see where technique use shifted:

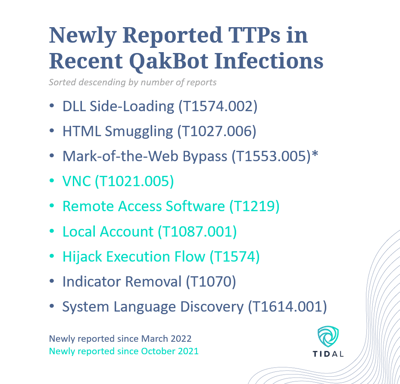

The following graphic summarizes the key techniques newly reported during each time period:

The Community Edition enables intuitive pivoting and overlays of defensive capabilities aligned with the same adversary techniques described in threat intelligence reporting. Our top guidance around the key techniques discussed in this blog (and covered in the linked QakBot Technique Sets) includes:

- Delivery: Most QakBot infections begin with malicious file delivery via phishing, including spearphishing attachments and spearphishing links. Robust email security and anti-phishing capabilities are recommended to mitigate these first stages of most QakBot attacks. User training and awareness around current phishing techniques is also highly encouraged. In an effort to further trick victims, QakBot is known to hijack legitimate email threads for initial malware delivery, either by compromising legitimate accounts, and recently by hijacking external/third-party email threads.

- User Execution: Macro-based techniques observed during the first phase of QakBot’s recent activity typically relied on users manually clicking to enable macros, while later attacks used email content themes that lured users into downloading attachments and opening one or even multiple downloaded files. Mitigations around user interaction and execution of suspicious files and links, including blocking of certain executables not typically seen in the environment and user training and awareness, are highly recommended.

- Initial Footholds: While writing detections for all possible variations of HTML Smuggling may be challenging, Microsoft suggests policies around automatic Javascript code execution and other mitigations here. Red Canary published an excellent explainer and defensive guidance around attacks leveraging ISO files to bypass MotW protections, and Huntress recently shared an approach to disable ISO mounting by default entirely. We were only able to identify a limited amount of defensive guidance around the latest, yet-unpatched MotW bypass technique involving files with “malformed” signatures. Keep in mind too that, despite new macro-related safeguards, threat actors have not entirely abandoned Excel and other macro-supported documents as malicious email attachments. Security teams should use this knowledge to inform hunting and detection prioritization.

- Regsvr32: The Regsvr32 technique had the highest overall reference count (eight) in the October 2021-October 2022 Technique Set discussed above, seven of which appeared in the recent April-October 2022 period. Adversaries abuse regsvr32.exe to proxy execution of malicious code. See the Regsvr32 Technique Details page to pivot to five Products with capabilities mapped to this technique, as well as 16 open-source Analytics. Red Canary’s recent Intelligence Insights also provides a good strategy for detecting a recent, specific QakBot implementation of this technique.

- Other Post-Exploit Techniques: Detection opportunities and other defensive capabilities exist around many of the other techniques not yet discussed here. Community Edition users can use the Technique Details pages to easily pivot to Products and Analytics aligned with adversary techniques. Readers are encouraged to focus especially on techniques most recently observed in association with QakBot, like those highlighted in the list in the graphic above. A few other recently observed post-exploit techniques include: Rundll32, Process Injection, Scheduled Task, System Binary Proxy Execution, File Deletion, and Impair Defenses. A set of Sigma analytics written directly around recent QakBot technique implementations, including DLL execution & loading, process injection, and scheduled tasks, can be found in Micah Babinski’s GitHub repository.

- Logging & Data Sources: The Technique Details pages can also be used to pivot to relevant Data Sources that, if logged, can provide visibility into instances of adversary technique use (you can also view the full list of ATT&CK Data Sources here and add them to your own matrix views).

- Branching Out: The Technique Details pages enable quick pivoting to relevant capabilities and analytics, saving time when trying to surface detections or capabilities that align directly with QakBot technique implementations (Procedures). They can also provide a springboard for testing and strengthening detections around other implementations of the same techniques. This is especially important as we consider how often and how quickly QakBot has evolved its technique set in recent times. Beyond just the Procedures observed in recent QakBot reporting, considering atomic testing, simulation, or emulation around variations on these technique implementations in an effort to proactively address possible TTP shifts by QakBot (and other actors and malware).

*Note: The Mark-of-the-Web Bypass technique was not explicitly mentioned in any of the source reporting we reviewed. Reported incident investigations may not have determined (or may not have disclosed) whether certain files possessed or did not possess MotW signatures. However, given the suspected use of ISO files to help bypass MotW safeguards, we are highlighting the technique here to represent the three reports in our sample that described QakBot infections involving ISO files.